Publications

www.rigaslaiks.com

Harijs Brants. Cellar Man, 2011

I even prefer the drawings to be in the same room with me, whatever room I happen to be in.

Harijs Brants

in drawings

Maybe it’s my natural wariness getting in touch with the unknown inside me. Maybe art is the ability to take what’s inside you, articulate it and make it visible… But, generally speaking, I don’t want to burden myself with the artist’s role.

Then, what kind of role do you want? A draughtsman’s, right?

Yeah, a draughtsman. To me, a draughtsman… Not every drawing is a work of art… in some sense I find that liberating. But you can think of it in a different way too. In a drawing, you make an entrance and an exit, a kind of door. It’s a door to what you might call childhood. It’s a way you manage to wonder, to get excited. When I was in art school, I really didn’t like doing all that summer work—all those watercolours—it was boring. But I’d find some pond, and then I could spend hours just poking tadpoles and leeches with a twig—these creatures are concealed in the water; they swim down deep and you can’t get at them. You know, there’s a kind of threat in that indifference nature has for man.[...]

Harijs Brants. Cellar Man, 2011

http://rigaslaiks.com/articles/harijs-brants/

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Harijs Brants. Drawing. 2010. Maksla XO Gallery

Harijs Brants: Drawing

The most important things in life are the invisible ones - friendship, joy, love, peace and so on. These things are not subject to human calculation; they cannot be bought for money or acquired by force or guile. Before they are expressed externally, these things happen in our inner world. This is a world where phenomena such as one's world view, notions of the structure of the universe and outlook on life are created and changed.

I call it my inner room. It's the place where my stories are born and live; a place where, in solitude, a person can encounter himself. Sometimes I get the feeling you can be more real there than in the outside world. The question then arises whether this other reality isn't more real than the usual, generally accepted reality?

For me drawing is a means whereby I can attempt to answer this question. Drawing is the opportunity to stay a while in the inner room and to experience it.

I find this unknown territory to be the most interesting to work with (to observe, explore); to strive to perceive and make out those moods I felt already back in my schooldays when I would shut myself off for several hours to draw.

I'm interested in transforming this invisible world into a visible one, to allow it to happen or prove to itself that it exists.

My drawings are like a continuation of the search for a new inner reality where the mind's eye depicts new variations of situations involving various images and assigning to them different and unusual functions and different interpretations of their meaning.

I have created a series of charcoal drawings that are mainly portraits.

For me the portrait is like an opportunity to open the door to another reality. If I can't draw the invisible world, then at least I can draw the images through which this world lives. In portraits our inner world looks at us.

The portrait in my opinion is the most suitable means for attempting to establish communication between these two realities - the visible and the invisible.

With a portrait one can achieve greater psychological intensity - a greater effect on the viewer. Important for me is the intrigue of the encounter that could happen between me and the viewer and that which has been depicted in the portrait.

I'm interested in what the viewers' faces will say.

I do much searching for people's faces in images. I look for people who aren't there. Then I draw them and there they are. They've arrived.

A realistic drawing method, a voluminous, tonally nuanced and scrupulously detailed drawing serves to achieve a greater impression of credibility in what has been depicted in the drawing and stimulates a sense of presence.

In the contemporary world (situation) of misunderstood values, this inner room is perhaps the most suitable place in which to find refuge from the tyranny of the pace of civilisation today. It is an invitation to stop and not become involved in the global confusion created by this tyranny. It is a place where, in contemplation, you can gain a deeper understanding of the order of things and renew the harmony with yourself.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Two Brants

Interviewed by Vilnis Vējš. 27/07/2012

http://www.arterritory.com/en/texts/interviews/1371-two_brants/

I meet with Harijs Brants before the opening of the exhibition featuring his sketches, scheduled for July 27 at the Cēsis Art Festival. During our conversation, Harijs leafs through the many pages covered in drawings and, at times, illustrates his point with one or two of them. However, it is his large-format charcoal drawings that have been reproduced the most often; they are much more involved, although in terms of theme – mellower. I attempt to get to the bottom of these differences.

Harijs: I have a feeling that drawing like this [sketching] has come to an end for me.

Vilnis: You mean fantasy pictures?

I call it a dumping ground for fantasy. I even tried finding key words with which to formulate it, and I wrote down all sorts of silly things.

For instance?

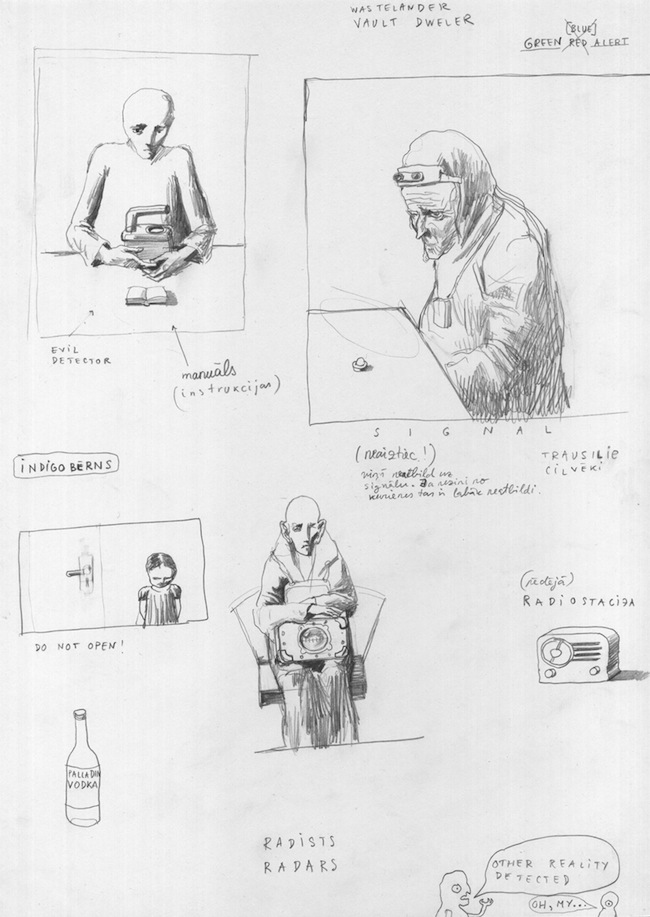

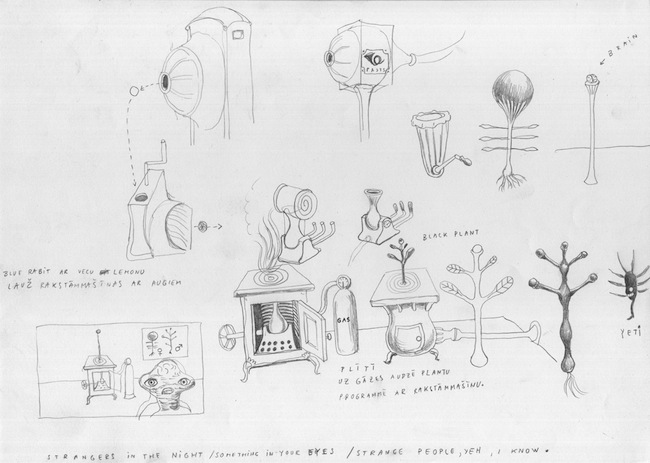

The mind in reverse. I read about the surrealists. What did they manage to pull out? Everything that's in the unconscious. The more paradoxically that things are connected, and the more that their meaning is changed, the better. Because it's more unrelated. See, it's quite a task. But the more I'd think about it, the more I started to not like this surrealism. Even though, if going by what's in the sketches, I should count myself as one of them [the surrealists], because there's a different function here. [Leafs through the sketches.] For instance, the Geiger counter here is a detector of evil. I should have given it that meaning. The person has it in his hands; I should have made the viewer think about it having some connection to evil. Maybe this is an interpretation, not quite surrealism...

I was interested in it all the time, but now... I think, if I continued to do this, it would be serving its own ends – it would be keeping something going that used to happen naturally.

Is it not coming to you anymore, or does it seem as if there's no point in putting it on paper?

It still comes. If I shake the “box”, stuff still comes out. But, if I get the idea that it should be drawn permanently, with coal... There's a technical problem as well. I still haven't been able to put a lot of things into one drawing. For instance, if the sketch has ten elements, then to put thirty in the drawing – so that they interact among each other on their own, and a process occurs, about which I don't really know what it is. It would be pure aesthetic enjoyment – it looks good, it has a good vibe. Unknown objects, well shaded, would make it seem as if there's some sort of world there. An aesthetic high, like it is with people who are really into antique things. For instance, transforming a 1920's lamp into something else – you don't know yourself what it is, and wonder at it. But now it seems as if its just another kind of burden; that instead of messing and fooling around, I'd like to understand more. That's why the portraits that I draw are an attempt at understanding. I don't know how much it is possible for a person to understand: Who is he? A drawing is an attempt to look into a person in a different way – not with the help of text, but with his visual image. A drawing is an attempt to either reflect, or to find something else, draw something out. So you see: all portraits have swept surrealism away. I've always had a dream to make a work that would be more like sketches. Make a work characteristic of surrealism. But I've always put that off, again and again. With coal, you can make two or three things, but if there are many, and they're small, then you'd have to sharpen the charcoal much too often. That's why in big works, there is one portrait, one wall; and that's tiring enough.

Would you get tired of drawings with many objects?

I would tire of them, yes. A person, a portrait – that's a serious goal that ensures an everlasting... what? It's disgusting overall, trying to describe with words that, which is being drawn. And the craziest thing is that today, I can tense up and try to explain something. But I am sure that after a year, I will be able to deny it all. That's why – is there any meaning in the part that is told? Does it even carry any weight?

There is – there's educational meaning.

You have 1000 sketches. How can you tell which ones could have the potential to be turned into a large drawing?

I have a feeling that there are so many because I'm really having a trying time. I used to not have a single drawing, just sketches. They were accumulating, and all just in A4 size. Now it's completely different. There are barely any sketches. There are just compositions – a person, half of a figure without arms, a portrait...

There aren't any sketches for the portraits?

No. Just for the one, which was said to look like Gints Gabrāns, even though the eyes were taken from the actor Tim Roth. I thought – I need one with a narrow arm... Hey, he looks a bit like you! I thought – I should really try and draw a portrait by myself, from heart [Harijs usually works with previously selected and mounted photographs – V.V.], and – yes, it came out just it should have – a bit “old-masterish”, posed at a three-quarter's turn. Then I cut out details from other pictures on the computer, and tried to put these details into the drawing. Well, I really taxed myself, but at the end, it ended up as my piece called “Behind the Wall”. Actually, those compositions that are in the sketches never get anywhere.

The Candy Eater. 102 x 61 cm. Coal on paper. 2012

I look at your sketches as if they were finished works, because they don't need anything else. The themes are comprehensible, and the shapes – laconic. The only problem – how can you bring it to the viewer? The sketches are very small.

There are several drawings on every page of A4. There was the idea – maybe they should have been made large-format from the start. But there's a problem – to make a drawing the way that I do now, I have to know how dark every space will be beforehand. If I haven't planned for it, and if I have to erase a bit, I can no longer get that spot the exact shade of gray that I need. Right away, the gradient of darkness jumps to +/- 20%. The tonality is very unstable. It's hard to reign in paper that has been roughed-up.

Then why do you draw your large-format works so finished?

I want to attain a believability that the drawing can become palpable. I want the drawing to approach the level of a photograph. But they're not photographic [the images], because there are a lot of things that are wrong. The shadows aren't right, the...

The Watcher. 102 x 58 cm. Coal on paper. 2012

We don't notice that.

Yes, its trickery. Drawing has the advantage of trickery – adapting a necessary shadow or shape. A photographer can't do that. A photographer has to get the lighting right, and the image is just one take. But when drawing, you can change the lighting, the angles and the proportions all the time. You can put the nose in a bit of a different angle, bring the eye out – according to need. In order to bring out the character, you can act freely, even if the image is realistic. Combining everything in terms of tonality and rhythm, believability arises. Although – if someone could make him (the person I have drawn) three-dimensional, it would be a really deformed human being. Not at all as good-looking as he looks in the drawing. Because as it turns out, character – expression, is what shows up in the drawing; but you can't say that about the person who was drawn.

But why couldn't you draw these sketches larger? Just the same way – using lines, but just, say – three times bigger? We can also understand images that aren't photographic.

When I used to draw caricatures – grotesque figures with pumped-up heads... I had a period when I was powerfully influenced by computer games – but that's old news. Cartoon characters have always interested me, which is why I've always drawn all sorts of comic figures. On the way to realism – although I never projected that I'd be making drawings as realistic as the ones I do now – at one point, there was a transition period: little girls with disproportionately large foreheads. I slid out of that stage somehow. But what was it that didn't satisfy me? Probably the fact that it wasn't really believable. That the image itself places boundaries. In the sense that it very strictly dictates what we see. When we can no longer interpret what is seen in the abstract – in the geometric cacophony. I have a tendency to deliver a concrete feeling to the viewer – that's an objection. But I haven't specially researched this myself. I just know that at some point, it became much more interesting to me.

In the sketch, we see, for example, a wrinkled old man sitting at a table; in front of him is a cup full of brains. An alien is sitting next to him. I won't ask about the story being told. A large picture could also be drawn with a line, a shadow hatched-in, and so on. Preserving the movements of the hand, which you completely remove in the finished work.

Ahh, to preserve that carelessness? I like to joke that to draw like me, you don't need any skill. It's very simple – If I don't draw for a year, the only thing I've lost is the ability to concentrate for long periods of time. And my fingers hurt if they're not used to it; I must have a thin palm. The whole of my assignment is to solve the relationship of “darker – lighter”, which I must do in any way possible. With a brush, by rubbing, scraping – it doesn't matter. I can poke with an eraser, make dots with a pencil. Any trick will do. There is not a single streak nor line – they must not show up in my work! If there is one somewhere, than that's a flaw. A line achieves concreteness; it has been visibly drawn. But that can't be! I've thought about how our sense of sight is ruined by the possibility of looking through a viewfinder, how it changes the conditions of perspective and everything else. But that's another story. A careless drawing wouldn't be interesting to me, because I probably need shadows and light; that the light is coming from somewhere. Although, I could make a drawing in which the sky is overcast. And I also want a lot of space.

How do you select the sketches to be exhibited?

For example [shows a sketch] – could this be called relatively good? This next one, for instance, is better. If there are three, then they form a composition that can be exhibited. And so on. There are, of course, duds!

You're known for your large works. They're mostly portraits – only at the very beginning did you draw something similar to skeletons. Could it be that you are assumed to be a portraitist, while the weirder, more surrealistic ideas are destined to stay as sketches?

Those portraits watch me. See, there's a psychologically therapeutic motif as well – maybe they're treating me? [Laughs] Something happened recently – I had been sketching all day. The good thing was that some sort of inner pressure had formed in me. Like in a pressure cooker, when a ventilation hole has to be opened to relieve the pressure. By working the whole day, the ventilation effect had worked. But on the other hand, I didn't feel well from that which was coming out. Instead of making happiness and surprise, it was depressing. Because in many of these ideas, there is something quite disconnected, in a bad sense. Chaos manifests there. I don't think that it's natural for a person to wish for chaos. Nevertheless, I think that fantasy is something of itself – with its intensity; I can't ignore it. But it is quite chaotic. You can work with it in several ways: it can be used, you can try to tame it, organize it, review it and put it into works with content. If the potential – the event – of chaos can be so used, then in my opinion, that's very good. But you can do it differently: be less controlling. Let it do its own thing. But then, when I've caught myself doing that, depression arises.

Once, after you had done the cartoon drawings for the show “Ice”, and I asked you about the role of erotica in your art, you distanced yourself from this topic because it wasn't relevant anymore. Now, when I show interest in the surrealistic and fantasy elements in your drawings, you distance yourself from these as well.

There is one way in which I can try to speak about that – by using a description of the process, how I approach a drawing, how I try to start. It's quite awful, in a sense, because the amount of material that is created during the process is so large and encompassing that it's very difficult to choose. Very often, two very similar characters compete with one another. Every character has sub-characters. As soon as I allow myself to look for them, they begin to multiply faster than I can sort through them – which is the best, which isn't. And they change even on a daily basis. Then I fall into a sort of labyrinth, and I have only one wish – to quickly get out of this situation and to focus on only one task, and bring that to a finish. These sketches give proof to the amount of work that I haven't been able to finish to any sort of degree. I could say that the sketches are good enough by themselves, and that that's just the way I draw; but then I, as a perfectionist, would have given up on my wish to bring something to a conclusion that would surprise me, as well. The surprise that I create for myself – by drawing an eye with expression, or in the details, or in a corner of the mouth – is much greater.

www.cesufestivals.lv

______________________________________________________________________________________________

REMIGIJUS VENCKUS: MATHEMATICAL NONEXISTENT UNREALISTICALLY REAL REALITY

Prior to the review of the Latvian artist Harijs Brants' (born in 1970) creative work, I would like to tell thestory of the fine art and photography relation. When photography drew the first breath, it seemed that the fine art would start floundering straightaway and eventually experience its own death in the prime of life. At the beginning of the new image revolution, the image, obtained practically instantly due to photographic technique, was fascinating in its verisimilitude. This enchantment forced the fine art itself to search for new portrayal, or in other words, the form design possibilities. It was necessary to expeditiously achieve a level of a different expression of the contents. This could take the two possible courses: a resistance to photographic reality and search for/implementation of the most hyperrealistic vision of the world possible or a retreat in search of possibilities for the expression of a pure sense, abstract rather that visual. It can be noted that these two tendencies are prevailing in the field of the contemporary fine art and even the visual arts.

It is possible to grapple with the reality of the world however one can seek a new and shocking view of the existent realistic world. The essential question hence arises whether the given possibility can actually be within reach. I dare say that if the Latvian painter H. Brants fails to actualize the present realistic vision of the world in his portraiture works, at least he is approaching the limit and spread field of the given world deformation possibilities through form deformation. Nonexistent unrealistic real reality seems to settle in his paintings. Accept this idea of mine as a provocation and an invitation to look at the world through the double glasses or to experience the astonishment of routinely met human images by means of double glazing. This world is moulded thanks to a perfectly mastered academic pencil. The suggestive, a little bit sensitively caricatured object being portrayed uncloses as a fish stuffed with various psychologisms. An anonymous fish at first glance, being all eyes in the painting, makes the beholder ask a rhetorical question: Am I a beholder or am I a being referred to the act of looking? A deep and impertinent look of characters does not domesticate and tame the beholder; a deep and impertinent look does not allow to repudiate the autonomicity of the own, the beholder's, look either; or, in other words, it does not allow avoiding the eye of the fish. Caricatured facial features and the most typical highlighted forms determine the perception, empathy and fear of the portrayed reality as of a surrrealistically dangerous fact of life. The behaviour of characters is moulded by means of connecting human anatomy and technologized culture. At this point, the fish turns into some kind of expressly developed, maybe even genetically derived creature. There, at the sight of Uncle Portrait (2006. Charcoal, paper, 23.6x25.9 cm) the imagination shudders in a twinkling. The Uncle resembles some sort of unearthly creature, the image of an alien which has been moulded and developed over the years by means of cinematography. Undoubtedly, the fish looking from the pictures imply the existence of a remarkable dialogue between the artist's creative act and science fiction. The bodies silhouetted against the dark of the night seem to be greeted as segments of the world which turns active at night and has been shaped on the basis of parallel darkness.

The artist is most fond of the central composition. The status of characters expressly sitting for portrait is exposed and emphasized. Some characters remind of and reveal themselves as sitting for both, classical portrait and portrait photography. There Flea (2010. Charcoal, paper, 55.5x51.8 cm) is portrayed as if in a photograph consistent with the standards of classical depiction. She seems to be captured almost frontally, boldly looking up straight into the viewer. However, the shoulder line betrays the character sitting sideways. This female person sitting for realistic portrait suggests certain associations with anthropological portraits created at the outset of photographic art and science. Photographs focused on the character's facial type itself/disposition. In the given directive, not elaborated, freely interpreted and not established another plane of the work or, in other words, the portrait background is surely justified. Grandfather Portrait (2008. Charcoal, paper, 49x40.2 cm) may evoke similar associations. The present portrait suggests that bodies undersized and heads overenlarged during the act of creation look interesting and uncomfortable. Most characters have protruding eyes as if continuously scrutinising the changes of reality and, under this scrutiny, determining a sense of surprise arising in the viewer's field of senses. This gaze of the eyes, very important to the artist, leads me to recall the French philosopher Jacques Derrida's reflections on the eyes and hands of a philosopher. According to J. Derrida, in human existence, these two parts of the body are ascribed the most privileges in getting acquainted/communicating with the objects/entities representing the world. According to the thinker, the eyes are not only the mirror of the soul but also the condition for the presence of/giving a sense to the world. A look always remains young and susceptible to visual information that is found in the existential human trivial round1. It should also be noted that the Lithuanian philosopher Arvydas Šliogeris is reluctant to consider eyes an instrument of the world cognition. Saying that tactilics is essential during the act of the world cognition, he suggests I should presume that the human hands are the only and the least questionable instrument of the world cognition2. The hands hardly are portrayed in the creative work of the Latvian artist yet the hands are implied by the look, the smile, the facial wrinkles at the surface that allow to predict the privilege of the world perception granted to the hands of the face owner (Agent and His Girlfriend Carlotta from Italy (Diptych), 2004. Charcoal, paper, 20x20 cm; Grandfather, 2008. Charcoal, paper, 49x40.2 cm; Flying Circus, 2009. Charcoal, paper, 98.5x60.5 cm).

In this review, I would also like to mention A. Šliogeris' ideas on art non-literally. The philosopher argues that art is close to science. Art, as well as science, involves many of the principles inherent in mathematics. When I first heard this idea, I wanted to resist maintaining that it was hardly possible to mathematize the inner feeling which determined the visual and the immersive planes of the work. However, after fathoming the philosopher's ideas and H. Brants' creative work system, I have to agree with A. Šliogeris' statement3. As I recall, the sculptor ceramicist Gintaras Martinionis has also said that a drawing, and especially anatomical one, is equivalent to higher mathematics. Today I realize that a drawing is based on artistic-mathematical dogmas. Since an academic drawing is something mathematical, consequently that something lingers between a feeling and the complete and absolute logic. H. Brants' drawing is an odd marking referred to mathematics.

Space and time in the painter's works are sort of suspended. The characters are almost separated from what could firmly state the work spacetime. Due to the titles and backgrounds of some paintings it can only be assumed that a certain moment belongs to Venice (Agent and His Girlfriend Carlotta from Italy (Diptych), 2004. Charcoal, paper, 20x20 cm) or to some other fancy everyday space. However, the background of characters in many works could be likened to the phenomenon of silence. I dare say that the silence is most perfectly poeticized and described in the texts and creative work of John Cage. Non-literal quotation: more silence, my ears have never heard so well before. Perhaps this silence is originally visualized in H. Brants' artistic system as well? You never know...

Art Critic - Remigijus Venckus, 23.06.2010. www.remigijus.venckus.eu

Vilnius Art Academy, Vytautas Magnus University, Šiauliai University

________________________

1 J. Derrida relates about the philosopher's eyes and hands in the film Derrida (2002) directed by Amy Ziering and Kirby Dick.

2 A. Šliogeris spoke about the hands as the prime instrument of the world cognition in a public seminar on 30 April 2010 where philosophy, politics and science relationship was discussed. The seminar was held at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science (Vilnius University).

3 Ibidem.

________________________________________________________________________________

Monks

2006, charcoal on paper, 100x70